Archaeological Evidence

For many years, scholars taught that Greek and Aramaic were the languages of Israel during the Second Temple period (530 BC to 70 AD). However, over the past fifty years, more and more evidence has surfaced to indicate that the language of the Jews in Israel during this time was Hebrew.

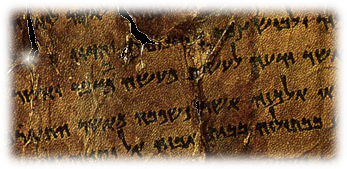

Simon Bar Kockba

In 135 AD, Simon Bar Kockba led the final revolt against the Romans. The image above is a fragment of a parchment that begins, “From Shimon Ben Kosiba to Yeshua Ben Galgoula and to the men of the fort, peace...” This is a letter from Kockba himself to one of his leaders in the revolt, and written in Hebrew, proof that Hebrew was used in Israel into the 2nd century AD.

Hebrew Coins

All coins minted in Israel during the 2nd Temple period (586 BC to 70 AD) and into the 2nd century AD, include inscriptions written in Hebrew (see above images).

The Dead Sea Scrolls

The many scrolls and thousands of fragments uncovered in the Dead Sea Caves were written between 100 BC and 70 AD. Some of these scrolls and fragments are parts of Biblical books, but others are works concerning day-to-day business. Of all the scrolls and fragments discovered thus far in the Dead Sea Caves, approximately 90% are written in Hebrew, while only 5% are in Aramaic and 5% in Greek. While most of the Hebrew inscriptions use the Late Hebrew script, some use the older Paleo-Hebrew script, such as we see in the image above of fragments from the book of Leviticus.

Textual Evidence

Paul Spoke Hebrew

When looking for evidence that Hebrew was the language of the Jews in the 1st century AD, the New Testament itself bears witness to the fact:

“And when he had given him permission, Paul, standing on the steps, motioned with his hand to the people. And when there was a great hush, he addressed them in the Hebrew language, saying: ‘Brothers and fathers, hear the defense that I now make before you.’ And when they heard that he was addressing them in the Hebrew language, they became even more quiet. And he said: ‘I am a Jew, born in Tarsus in Cilicia, but brought up in this city, educated at the feet of Gamaliel according to the strict manner of the law of our fathers, being zealous for God as all of you are this day.’” (Act 21:40-22:3, ESV)

The first thing we notice in this passage is that Paul, a Jew of the 1st century AD, was speaking to the “people” in Hebrew and they understood him.

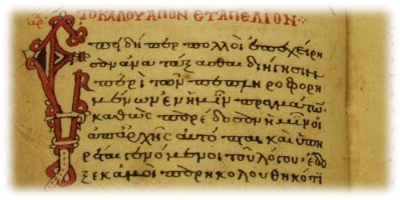

If the author of this work is correct in believing the New Testament was originally written in Hebrew, we can conclude that the original text would not have included the phrase, “he addressed them in the Hebrew language,” Instead, it was inserted into the Greek manuscript for clarification when it was being translated from the Hebrew.

The Maccabees

Two books of the Apocrypha, First Maccabees and Second Maccabees, give insight about the life and times of the Jewish people during the intertestamental period.

While it is generally accepted by Christians that the Jews spoke Greek during the New Testament period, the books of the Maccabees paint a very different picture.

The Maccabees preserve the story of the Jewish revolt, about 150 years before the time of the New Testament. The Greeks, led by Antiochus Epiphanes, conquered the land of Israel and forced the Jews to forsake their national heritage and Torah to begin adopting the Greek culture. Because of the Jews’ hatred for all things Greek, including the culture and language, Judah Maccabee led a revolt against Antiochus Epiphanes, expelling the Greeks and slaughtering those Jews who had adopted the Greek language and culture. This revolt demonstrated the extent of the Jews’ deep hatred for the Greek culture and language. Furthermore, it dispels the assumption that the Jews freely adopted the Greek language leading up to the New Testament period.

Josephus

Josephus, a 1st century Jewish historian, recorded Jewish life and sentiment during the time of the New Testament. In his work, Antiquity of the Jews, he writes the following:

“I have also taken a great deal of pains to obtain the learning of the Greeks, and understanding the elements of the Greek language, although I have so long accustomed myself to speak our own language that I cannot pronounce Greek with sufficient exactness: for our nation does not encourage those that learn the languages of many nations.” (Josephus, Ant.20.11.2)

Josephus makes it very clear that the Jewish culture had a strong aversion to the Greek culture and language, and we learn that most Jews could not speak Greek, contradicting the notion that the Jews universally spoke Greek in the 1st century AD.

Historical Evidence

Scholars in Israel note that it often takes about 50 years for new evidence accepted there to reach the mainstream in the West. For example, discoveries from around 1970s are only now becoming widely recognized in the West. One such case involves the language of the New Testament era Jews. About 50 years ago, Israeli scholarship reached a consensus that Hebrew was still actively spoken during that period, but only recently has this view begun appearing in Western sources such as we find in Wikipedia:

In the first half of the 20th century, most scholars followed Abraham Geiger and Gustaf Dalman in thinking that Aramaic became a spoken language in the land of Israel as early as the beginning of Israel's Hellenistic period in the 4th century BCE, and that as a corollary Hebrew ceased to function as a spoken language around the same time…

During the latter half of the 20th century, accumulating archaeological evidence and especially linguistic analysis of the Dead Sea Scrolls has disproven that view. The Dead Sea Scrolls, uncovered in 1946–1948 near Qumran revealed ancient Jewish texts overwhelmingly in Hebrew, not Aramaic. The Qumran scrolls indicate that Hebrew texts were readily understandable to the average Jew, and that the language had evolved since Biblical times as spoken languages do…

Alongside Aramaic, Hebrew co-existed within Israel as a spoken language. Most scholars now date the demise of Hebrew as a spoken language to the end of the Roman period, or about 200 CE. It continued on as a literary language down through the Byzantine period from the 4th century CE.

| Join my mail list and discover new insights into the language and culture of the Bible — plus, get a FREE e-book |