Articles & Video

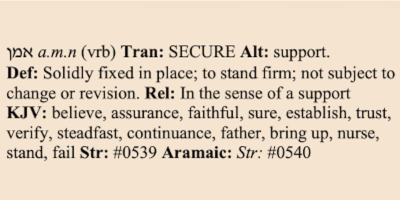

| About the Lexicon (Article) This lexicon is unique in that it connects each Hebrew word with its related roots and words and the cultural background of these roots and words. |

| How to use Benner's Lexicon of Biblical Hebrew (Article) Instructions on how to effectively use this lexicon to find the cultural background and meaning of Hebrew words. |

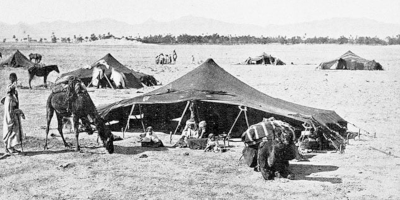

| The Language and Culture Connection (Article) Exploring the purpose of understanding how language shapes thought and culture, showing why recovering the ancient Hebrew perspective is essential for interpreting the Bible as its original authors intended. |

Video: What does the Hebrew word for "spirit" have to do with the "moon" and a "traveler?"

Testimonials

“An excellent tool to help develop understanding of the Ancient Hebrew language.”

“Now when I read the Bible, it's almost like watching a movie.”

“This lexicon is a must-have for serious Bible students.”